Sixty years ago, when the gu ns of war stopped firing in Korea, I was a staff writer for Time magazine in New York. I had spent two years as a Korea war correspondent, so Time’s foreign news editor asked me to write about what the American G.I. had seen and heard and felt in the war. My article appeared in the August 3, 1953 issue of Time and it earned me a nomination for an Overseas Press Club award. With the permission of Time Inc., I re-publish it here on the anniversary of the Korean armistice.

ns of war stopped firing in Korea, I was a staff writer for Time magazine in New York. I had spent two years as a Korea war correspondent, so Time’s foreign news editor asked me to write about what the American G.I. had seen and heard and felt in the war. My article appeared in the August 3, 1953 issue of Time and it earned me a nomination for an Overseas Press Club award. With the permission of Time Inc., I re-publish it here on the anniversary of the Korean armistice.

How the Ball Bounced

More than a million Americans, many still in their teens, fought, and survived, the Korean War. The G.I. never quite understood what this particularly bewildering war was all about. But he fought well, and reached his own understanding of Korea by personal, painful, ugly experience.

For one thing, he understood death. There was the first mound of corpses by the roadside, caked with dried blood, open mouths frozen in a scream. His sergeant said: “Don’t get shook up. They’re just Koreans.” Or there were muddy U.S. Army boots protruding awkwardly from under a blanket as a litter jeep bounced down the road from the front. Or in the rain, as he climbed his first Korean hill, there was the glistening poncho stretched over the two men sleeping near the trail—and then he realized that they were asleep forever.

Death reached closer. He had to tell the captain: “He was lying in his hole, all curled up. I guess the round just dropped in on top of him.” Afterwards, he and the rest of the squad had to decide what to do with the last letter the man had written before the round dropped in on him. “Send it home,” said the chaplain, “his Mom will want to know what he was thinking before he died.”

The Why. The G.I., like any other soldier, was afraid of death, which came suddenly, and always at the wrong time. A man in his company was blown up just after he got a telegram that told him he had a new son, his first. “The American soldier has only one fault,” said a platoon leader. “He has too much to live for.” Many men said: “I don’t want to be a hero, I just want to be alive.” Nevertheless, there were plenty of heroes before it was over. Not wanting to die, the G.I. newly on the line took a while to discover what made a man risk death.

But eventually, he understood why a medic threw himself between a patient and a grenade. He understood the private who could have abandoned his hole, but stood up throwing back Chinese hand grenades before they exploded—until he misjudged one. And the corporal, with four bullets in his chest, who was told: “Take a stretcher; you’ll die if you walk down.” “Yeah,” he replied, “send four guys back to carry me and they’ll all get clobbered. I’ll make it.” And he did. Those were the cool heroes, sacrificing themselves, not to “halt aggression” or “fight Communism,” but out of elemental loyalty to the outfit, and to the other men around them.

There was another kind of hero forged by the heat and pressure of battle. There was the private, foot all but blown off, chest punctured with machine-gun bullets, face mangled by a mortar chunk, who kept going until he got nearly to the top of the ridge. There, he died, and only then fell down. There were the two Kentuckians who rushed up a hill screaming hillbilly songs and dived into a North Korean bunker with their hand grenades, blowing it up. There were also men who went to pieces in the strain of battle, and dashed forward, screaming and crying, to be cut down by the enemy. Other panic-stricken men “bugged out,” or groveled in their foxholes, clawing at the earth. He turned away and hoped that would not happen to him.

The Koreans. The courage of the South Koreans was a different kind: to G.I.s it seemed not sacrificial, not fanatical, but resigned. One bearded old “Papa-san” of the Korean Service Corps “choogied” mortar ammunition up one hill, then caught a bullet in his chest as he was starting back down the trail for more. He lay by the mortar position, blood leaking from his chest, and passed shells to the shorthanded mortar crew as he died. Each time the tube fired, the old man muttered a Korean word, but the Americans on the mortar never knew what it was.

The Korean language is difficult, and the G.I. did not have the time and energy to pick up more than a few words. So he learned about the Koreans from what he saw, and through the Pidgin English the Koreans themselves put together. In the back of a truck, choking on the fine, powdery Korean dust, wondering how the Koreans could live in it, he suddenly saw a Korean coughing too, and he realized that the armies had stirred up the dust and the Koreans suffered from it “same-same” as he.

In the cities, the children clustered around him, waist-high and squalling, grimy fists tugging at his sleeve. “Hey, sah-jint, you want buy? You want numbah-one shoeshine? You want change-ee money, sah-jint? You want nice girl, maybe? Hey, sah-jint, you want numbah-one nice virgin girl?” Sometimes they snatched a pen or wallet from his pocket and scampered off down an ill-smelling alley. Sometimes the crippled ones, scabrous and foul with dirt, hunched themselves into his path and clawed frantically at his trouser leg. “Money, skoshi money, little money! Three days, eat have-a-no, sah-jint.”

He walked through the muddy, stinking, raucous market areas, holding his hand on his wallet, buying cheap souvenirs. There were fur caps and fur-lined boots, little carved figures, thousands of leather holsters and wallets, brass ashtrays and gaudy silk antimacassars, embroidered with the word “Korea,” and the year. Behind the main streets, in the narrow alleys, he could purchase—with “no sweat”—scarce Army supplies, like light bulbs and radio batteries. There were piles of leather jackets from U.S. mail-order houses, gleaming rows of cheap watches smuggled in from Japan, gay shelves of Japanese cosmetics, even stacks of C-ration cans. “You want buy, sah-jint? Numbah one.”

That was in the cities. In the country, he held his breath when he passed farmers fertilizing their paddies with excrement from the “honey buckets.” “Mama-sans” squatted on riverbanks, pounding their washing with sticks on the wet, flat stones, while their black-haired infants slumbered on their backs. Old men with black “birdcage” hats and two-foot-long pipes squatted, low down on their haunches, in front of ruined huts. Refugees, haggard and desperate, journeyed a long road, furniture and bedding piled high on “A-frame” and head, bound for a filthy cardboard shack which they would then call home. Before entering it, they would remove their shoes.

The prospect of death he learned to accept, and he seldom talked about it. But he could gripe about the hardships. Each echelon claimed that the men to the rear were “fat” with luxuries. The man on the line envied the man at battalion because he usually slept on a cot and lived in a tent and had three hot meals a day. Battalion thought regiment “had it made” because there the men rode around in jeeps. The soldier assigned to regiment wished he was farther back at division, where it was safer, where there were showers, Korean houseboys to do the laundry, and movies almost every night. The man at division figured the corps headquarters soldier “had it knocked” with his PX, his girls, and “tak-san” (much) beer. At corps, they envied Army’s warm buildings, big PX, recreation programs, coffee and doughnut canteens, and “Stateside” Red Cross girls. The G.I.s at Army headquarters would rather have been in Japan, or else close to the front collecting four rotation points a month. But everybody wanted to go home.

R & R. The G.I. was homesick the minute he hit Korea. Around the sputtering Coleman lanterns in the bunker, on the long, dusty truck rides that bruised his bones, he talked of “The Big R” (rotation) and “The Little R” (rest and rehabilitation leave in Japan). He knew to the day when he could expect to go home —”if too much stuff doesn’t hit the fan and use up all the replacements,” or if the brass didn’t “push the panic button” and freeze rotation for a while.

He served his time and left Korea. His outfit stayed on. There was no “duration” to limit or extend his stay. The veterans of World War II went home by the hundreds of thousands in the ranks of their outfits, with a sense of accomplishment and the prospect of a big welcome—maybe a parade. They had suffered and won. The veterans of Korea trickled back individually, with a sense of relief at being alive. They have merely suffered.

The returning veteran of 1945 was a man of hope; his enemy was beaten, his target—Tokyo or Berlin—was reached. He was ready for a brave new world of peace and plenty. His younger brothers, resigned to the ugly old world of war and greed, shout no message. They argue about whether the war should have been started, whether it should have been carried into China or stopped at the 38th parallel, whether Van Fleet or MacArthur or the White House had the right solution—and they don’t pretend to know all the answers. All that binds them is their common understanding of the steep ridges and the stinking paddies and the swift night attacks from the north.

In gathering places across the U.S. they recognize each other when they hear such terms as “bahli-bahli” (“hurry up”), or “no sweat.” Their password is a mangled version of Arirang, the Korean folksong taught them on a quiet night by ROK soldiers in the bunkers. The badge of their fraternity is the fatalism by which they say, when things go wrong: “That’s the way the ball bounces.”

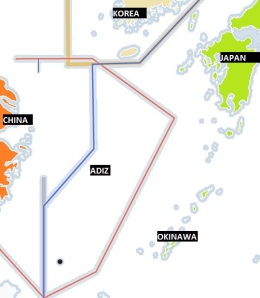

China has been accused of attempting to dominate the Pacific Ocean by proclaiming an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) that extends about 200 miles off the China coast. The Chinese ADIZ is “provocative,” U.S. and Japanese officials have declared, because it overlaps an ADIZ established by Japan and because it covers the uninhabited rocky islands that Japan and China have been arguing about. The Japanese ADIZ covers those islands too, but that is not provocative, of course, because Japan….well, because Japan is… well, Japan is not China, that must be why.

China has been accused of attempting to dominate the Pacific Ocean by proclaiming an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) that extends about 200 miles off the China coast. The Chinese ADIZ is “provocative,” U.S. and Japanese officials have declared, because it overlaps an ADIZ established by Japan and because it covers the uninhabited rocky islands that Japan and China have been arguing about. The Japanese ADIZ covers those islands too, but that is not provocative, of course, because Japan….well, because Japan is… well, Japan is not China, that must be why.